William Eggleston

William Eggleston

Occasionally, when he was much younger, the celebrated American photographer William Eggleston used to turn off the lights at his home in Memphis, Tennessee and shoot guns in the dark for fun. "The house was riddled with holes made by $6,000 antique shotguns," an acquaintance once revealed. He is often described by journalists as a heavy-drinking hellraiser, with a weakness for Savile Row suits and expensive cars – over the years, he has owned a Ferrari, a Jaguar, a Bentley and a Rolls-Royce.

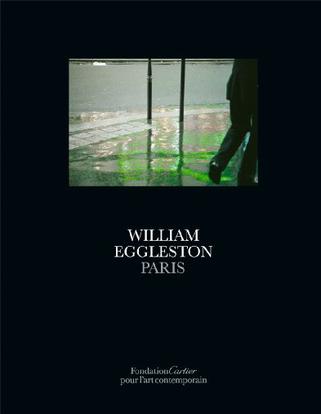

True to form, after a long lunch with the German fashion photographer Juergen Teller, Eggleston turns up late for our interview in the Fondation Cartier, a museum in Paris devoted to contemporary art, where a new series of his photographs has just opened. A few months short of his 70th birthday, he is dressed immaculately in a navy suit, his brown brogues buffed to a shine – yet there is a whiff of something decidedly louche about him. He slumps in a leather sofa that has been placed in the foyer to his exhibition, not far from a baby grand (Eggleston is an accomplished pianist, and a devotee of Bach). A solitary pearl of perspiration rolls down his forehead.He is here to talk about his new work, his third commission from the Fondation Cartier, which most recently invited him to document Paris in a series of photographs. In the early Sixties, Eggleston took his young wife to the French capital hoping to come away with a suite of meaningful pictures, but he felt blocked, and left with nothing. Over the past three years, however, he has returned to the city several times, and stalked its streets, snapping away on his Leica.

During this period, he amassed thousands of pictures, from which the foundation's director, Hervé Chandès, selected 70 for the show. As Eggleston tells me, with some effort, as though dredging up the words from the depths of his soul, "I'm not particular. I don't have favourite pictures." He pauses, before continuing: "To me, the whole project, no matter what size, is the work."

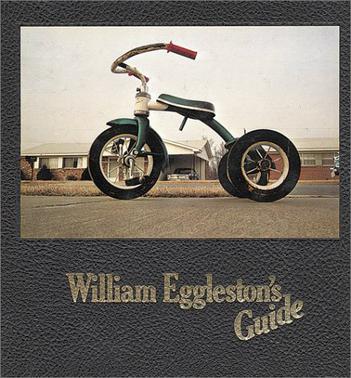

Born into a wealthy Southern family (he has never needed to earn money), and raised on a former cotton plantation, Eggleston is credited as a pioneer of colour photography. His breakthrough exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1976 showed that colour photography could be an artistic, and not merely a commercial, medium. At first, the critics condemned his seemingly casual snapshots of everyday life in the Deep South as "perfectly banal". But the book that accompanied the exhibition, William Eggleston's Guide, proved extremely influential. His free-and-easy images, shot quickly without a tripod from quirky angles, glow with gorgeous colour. They were soon seen as refreshingly democratic in both form and content, a tonic to the stagy, studio-manipulated fine-art photography, which, before 1976, had generally been black and white. "I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around," Eggleston once said, "that nothing was more important or less important."

The new Parisian pictures continue in this vein. With typical perversity, Eggleston refuses to frame a picture that might result in a visual cliché. There are no shots of famous monuments, no pictures of wrought-iron signs for the Métro. Photographs of chic Parisians strolling through the Jardin du Luxembourg are nowhere to be seen.

Instead, there are images of packing crates and graffiti, of a woman begging outside the entrance to the Bastille Métro station, of neon-green light reflected in a puddle of rainwater on a dingy street corner, and of cheap shops selling gaudy tat. Eggleston is drawn to the city's neglected nooks, and often shoots close-up so that it is not immediately clear what the subject of a particular picture is. In fact, many of his photographs could have been taken in any city in the world. Somehow I doubt that they will be used by the Parisian Office du Tourisme any time soon.

Was he consciously trying to avoid clichés? "Not really," he says in his slow, gravelly baritone. But surely he was aware of the masters of photography who documented Paris during the 20th century – people like Eugène Atget and Henri Cartier-Bresson? "I knew about them," he says. "That was in the back of my mind." Yet, as he explains in the exhibition guide, he approached Paris as if it was just anywhere: "That resulted in pictures infused with a little mystery. You're not quite sure: is this Paris, Mexico City, elsewhere? I didn't change my style for Paris. I just did as always, used the same approach."

Eggleston's photographs of Paris will not be to everyone's taste. At first glance, they seem nondescript. But I love the fact that they are worlds apart from the familiar iconography of this famous city. Eggleston's aesthetic is wonky, half-cocked, provisional – and energetic. His pictures feel fresh and true: tiny scraps of reality ripped from the everyday fabric of life in a modern metropolis. He is capable of transforming the trivial into the transcendental, of wresting beauty from unexpected and overlooked places.

His new photographs are also eminently formal, almost abstract. In many of them, bold splashes of colour divide the image into sections, like a vibrant geometric painting by one of the Suprematists. Eggleston only ever takes a picture of something once, which means that his grasp of composition is all the more phenomenal because he never poses his images. His sense of colour would turn most artists, well, green with envy.

"Everything must work in concert," he says. "Composition is important but so are many other things, from content to the way colours work with or against each other."

Alongside his series of Parisian photographs, Eggleston is also showing 40 abstract paintings and drawings for the first time – colourful squiggles that were mostly created using felt-tip pens. He has drawn like this since he was a child (he didn't become interested in photography until he was at the University of Mississippi, where he became captivated by the work of Cartier-Bresson), and these pictures owe a clear debt to Kandinsky, one of Eggleston's favourite artists. They also feel exceptionally musical, brimming with rhythmic swirls.

"I like that idea," he tells me, "though I don't think about that consciously. I like to think that my works flow like music. That may be one reason I work in large groups versus one picture of one thing, it's the flow of the whole series that counts. I think when Paris is finished, it will flow."

As things stand, the project is far from finished. "Even though I now have several thousand pictures [of Paris], I still feel I have just barely begun," he says. "It's a big project. I hope it will be my crowning achievement." But, when pressed on what else he plans to document, he clams up. "I don't have anything in mind," he says. "Nothing more I can say would make any sense yet, because the series is not finished. I'm interested in wherever I go." He pauses. "There's no shortage of visually interesting places to me."

It's clear that Eggleston hates talking about his work. Throughout the interview, he is courteous but also reticent, like a well-dressed screen idol who never uses three words when one will do. He is also keen to avoid discussing the meaning of his work, and refuses to talk about individual images. His silence piques my curiosity. Why does he hate to talk about his photographs? "I don't know how to," he says, as if it's the most obvious thing in the world. "I'm not busy talking, and I don't write – because I'm busy making images."