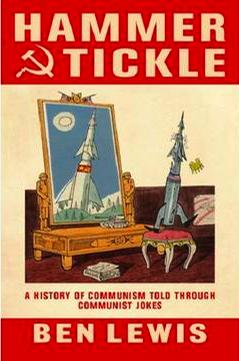

Hammer & Tickle

Ben Lewis

Hammer & Tickle*: A History of Communism Told Through Communist Jokes.

《红旗下的谈笑–政治笑话中的苏联史》

JOKES under communism were not just a welcome contrast to the dreariness of everyday life; they also helped undermine it. For example. “How do you deal with mice in the Kremlin?” “Put up a sign saying ‘collective farm’. Then half the mice will starve and the others will run away.”

苏联的共产主义社会中,政治笑话不仅是民众在无聊生活中找的乐子,它们也帮助民众化解苦难。比如这个:”如何赶跑克里姆林宫里的老鼠?”"在里面放个标牌,写上‘集体农场’四字,不多久大半老鼠会饿死,剩下的都逃之夭夭了。”

Ben Lewis has collated some of the best, and best-known, jokes that were told under more than seven decades of communist rule. His work is based on more than 40 previously published collections ranging from underground selections, to those published by anti-communist émigrés, and a large sprinkling that appeared after 1989, once it was safe to air them.

Ben Lewis的《红旗下的谈笑》收录并校订了一些优秀的政治笑话,它们在苏联七十多年统治下广为人知。这本书取材来自市面上四十多册的笑话集子,从当时地下流传的选集,到反共移民出版的著作,乃至1989年之后涌现的一大批书(那时候已经可以安全传播这些笑话了)。

Most make you giggle and groan in equal measure. It is worth remembering that in some countries and some eras, being overheard telling or laughing at just one of these jokes could mean you died in a labour camp; there are plenty of jokes about that too. “Who built the White Sea canal [Stalin’s single most murderous slave-labour project]?” “The left bank was built by those who told the jokes, and the right bank by those who listened.”

书中大部分笑话令人笑过之后掩卷叹息。需知在某些国家、某些历史时期,讲笑话者若被有心人偷听或者仅仅无意谈笑之间就意味着你可能招来杀身之祸。书中就收录了许多有关于此的笑话–”是谁建了白海运河(斯大林草菅人命,下令劳改犯修建的一项工事)?”"说笑话的人建了左岸,听笑话的人建了右岸。”

But the aim of “Hammer & Tickle” is not just to be amusing and poignant, but also to instruct. The author makes the (to him) rather depressing discovery that most communist-era jokes were just recycled versions of older ones. Take this example, which is told twice in the book: a flock of sheep approaches the Finnish border in a panic, pleading to be allowed entry. “Beria [Stalin’s secret police chief] has ordered the arrest of all elephants,” they explain. “But you’re not elephants,” reply the Finnish border guards in puzzlement. “Yes, but try explaining that to Beria.” That sounds spot-on for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. But it can be traced to a Persian poet in 12th-century Arabia, where it involves a fox running away from a royal ordinance that in theory applies only to donkeys.

但《红旗下的谈笑》一书并非简单陈述这些可笑可叹之事,作者还立意于说教。他发现大部分共产主义时代的笑话都仅仅是过去说法的翻版,这让他很失落。比如这个在书中出现两次的笑话:一群惊慌的羊来到芬兰边界,请求进入对方国境,说:”贝利亚(斯大林的秘密警察头子)下令逮捕所有的大象。”芬兰边防士兵惊道:”可你们不是大象呀!”"没错,不过你得跟贝利亚解释。”这个笑话产生于1930年代的苏联,但可以追根溯源至12世纪一位波斯诗人的著作,它就讲到只针对猴子的忠诚诫令导致狐狸逃亡的故事。

Unfortunately, Mr Lewis is not content to laugh and remember. He wants a “serious comparative study” of the subject. It is tempting to think that he is joking, and that his theoretical elaborations about the true significance of communist-era jokes are a subtle parody of the way that modern literary critics so often miss the point of the texts they write about. It is almost comical to read his po-faced but pointless consideration of whether jokes about Stalin predated Stalin’s own jokes-almost comical, but not quite.

可惜Lewis先生并不满足于记录,他弄巧成拙,想对这些笑话做”严肃的比较学研究”。如果他只是开玩笑那也罢了,大家会以为他这么说只是想假模假样的构建复杂的理论,用来阐述这些笑话的重大意义,借此巧妙地嘲讽当下的某些批评家——他们通常对自己研究的文本一窍不通。然而当他一本正经要考证关于斯大林的笑话是否出现在斯大林之前时,那种不得要领的劲儿让人喷饭,却多少有点无趣。

If Mr Lewis is indeed joking, he pushes it too far. The potted histories of communism he provides as context are leaden and sometimes sloppy. The travelogue of his meetings with jokesters across the Eastern block is fun at first but then becomes dull. In particular, the conceit of linking his research to the ups and downs of his relationship with a tiresomely pro-communist (and humourless) girlfriend from East Germany is jarringly intrusive and self-referential.

如果Lewis先生真是在开玩笑,那他未免矫枉过正了。他阐释笑话,给出的却是模糊乃至粗糙的历史语境。他的旅行见闻讲座,描述了他与来自东欧各个共产主义国家的笑话提供者会面的场景,一开始引人发噱,之后却变得无聊。此外,他还认为自己的研究历程伴随着他与女友感情的起起落落——他说女朋来自东德,是一名支持共产主义的讨厌鬼(并且没有幽默感)——这样的描写与全书非常不协调,并且过于私人化了。

No matter: rather than worrying about whether humour was ultimately a safety-valve for communism or subversive of it, the reader can skip ruthlessly and concentrate on the jokes, and the remarks people have made about them. “Jokes against the Party constitute agitation against the Party,” raged Matvei Shkiriatov, a zealous Stalinist, at a Central Committee Meeting in January 1933. That was echoed by Hitler’s propaganda chief, Josef Goebbels, in 1939, when he wrote: “We will eradicate the political joke.” But they didn’t.

不过没关系,读者没有必要关心这些笑话究竟是不是民众不满共产主义的出气筒或颠覆政权的炮弹,你大可跳过这部分,并专注政治笑话本身及政客对它们的评论。狂热的斯大林主义者Matvei Shkiriatov就在1993年1月的一次中央委员会上盛怒咆哮:”取笑我党就是反党!”1939年,这咆哮在希特勒的宣传部长约瑟夫•戈培尔那儿激起回声,他写道:”要奋力消灭政治笑话。”他最终未能成功。

Many of the jokes told about past Soviet leaders are now told about Vladimir Putin (Stalin appears to him in a dream and says: “I have two bits of advice for you: kill your opponents and paint the Kremlin blue.” Putin asks, “Why blue?”). The world would be a poorer place without the jokes sparked by ridiculous yet ruthless rulers. But Russia would be a lot happier.

如今,许多笑话中的苏联领导人换成了普京(有一个是这么说的:斯大林托梦普京:”我给你两条小小的建议:整死你的对手并把克里姆林宫漆成蓝色。”普京问:”为何是蓝色?”*)这些笑话产生于荒诞而粗暴的社会,世界如果没有了它们将会很无趣,不过现在的俄罗斯人好歹开心许多。