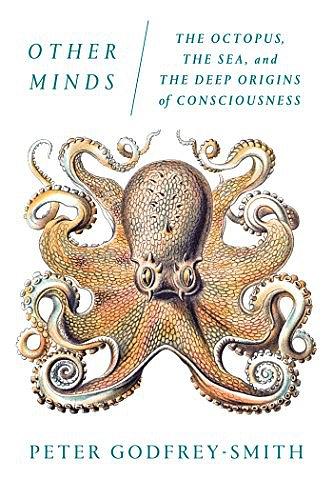

Although mammals and birds are widely regarded to be the smartest creatures on earth, it has lately become clear that a very distant branch of the tree of life has also sprouted higher intelligence: the cephalopods, consisting of the squid, the cuttlefish, and above all the octopus. In captivity, octopuses have been known to keep tabs on individual human keepers, raid neighboring tanks for food, turn off lightbulbs by spouting jets of water, plug drains, and make daring escapes. How is that a creature with such gifts evolved through an evolutionary lineage so radically distant from our own? What does it mean that evolution built minds not once, but at least twice? The octopus is the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien. What can we learn from the encounter?

In Other Minds, Peter Godfrey-Smith, a distinguished philosopher of science and skilled scuba diver, tells a bold new story of how subjective experience crept into being—how nature became aware of itself. As Godfrey-Smith stresses, it is a story that largely occurs in the ocean, where animals first appeared. Tracking the mind’s fitful development, Godfrey-Smith shows how unruly clumps of seaborne cells began living together and became capable of sensing, acting, and signaling. As these primitive organisms became more entangled with others, they grew more complicated. The first nervous systems evolved, probably in ancient relatives of jellyfish; later on, the cephalopods, which began as inconspicuous mollusks, abandoned their shells and rose above the ocean floor, searching for prey, and acquiring the greater intelligence needed to do so. Taking an independent route, mammals and birds later began their own evolutionary journey.

But what kind of intelligence do cephalopods possess? Drawing on the latest scientific research and his own scuba-diving adventures, Godfrey-Smith probes the many mysteries that surround the lineage. How did the octopus, a solitary creature with little social life, become so smart? What is it like to have eight tentacles that are so packed with neurons that they virtually “think for themselves”? What happens when some octopuses abandon their hermit-like ways and congregate together, as they do in a unique location off the coast of Australia? And how does the cephalopod mind differ from the mammal mind, which took its own path—a path that eventually gave rise to an especially rich form of consciousness?

By tracing the question of inner life back to its roots and comparing human beings with our most remarkable animal relatives, Godfrey-Smith casts crucial new light on the octopus mind—and on our own.

1、追日是作者栎年创作的原创作品,下载链接均为网友上传的的网盘链接!

2、相识电子书提供优质免费的txt、pdf等下载链接,所有电子书均为完整版!

-

美丽雉科废青的评论这时候我就想问,凭什么因为鱿鱼之间少有社交活动,就觉得它们的皮肤LED并非交流信号呢?不可以跟其它生物/微生物交流么?

-

Reader(被停權)的评论章魚的八支腕足(日本人譯作觸手,想是參考釋教,但弄巧成拙,恰如觸手請經)所分別/共同感知乃至意識到的世界什麼模樣,人類在正常情況下永難瞭解。但是我們總能推測它不會是什麼模樣----我猜它就不能是水形物語那副模樣:貌似豐贍的象喻一提溜起來全連成一氣指向一組簡單的概念,如心使臂,如臂使指,太呆板了,太中產了。

-

佛法GEEK的评论作者骗我养触手系列,而且很成功,的确被章鱼魅惑了。章鱼这种“全身都是脑”的动物,对于人类的“大脑=中枢司令塔”的理解范式绝对是个挑战。本书看点是从进化角度提出了意识/主观经验产生的假说。缺点是对动物行为学的推测性解释太多了(尤其是他自己去潜水时的观察),并不太能说服人。

-

sonatanegra的评论fingers crossed

-

鸟的评论无甚特别的科普

-

一捺的评论the evolutionary journey of the subjective experience 章鱼真的是神奇一般的动物啊

-

快乐分裂的评论书店的推荐是手写的挪威语,结账时店员小姐姐热心告诉我,意思是看完之后你还会去吃章鱼吗,我看完了回答一下,会。哈哈哈哈…

-

cherry it up的评论animal psychology is a very exciting topic. this book is very inspiring in terms of helping me imagine a cyborgian creature in our society. but the research itself seems too wishy-washy and far from serious, hard science -- but it's an octopus book written by a philosopher, how else should i expect it to be?

-

陈不行的评论没什么意思

-

狐狸新聞的评论Nothing is sadder than seeing an unfinished business. With so much left undone and unrealized, we feel intensely empathetic to our 8-armed friend. What’s living and where does evolution take us? Does it going anywhere? And what’s our trade - if there’s one for us too.